The Peasants’ Revolt

Revolution in Smithfield

How many times over the last three months has the word “unprecedented” been used in conversations about the City? Even the wisest and oldest heads in the various firms and businesses that make up the Square Mile are struggling to think of a time when the normally busy streets have been so completely abandoned and the usual inhabitants are instead crouched over kitchen tables or sat in home offices balancing children in one hand and conference calls in the other.

I am sure I am not the only person to question whether the way we did business six short months ago can ever really return. But, as a self confessed history fanatic, it has got me thinking about other occasions where the City has gone through tumultuous times and come out the other side, different but not diminished.

This is the first of a short series of five articles considering a number of incidents when the City has gone through dramatic change and where I attempt to draw some parallels between the recovery that London made and the recovery we might see over the next few years.

I hope this might explain why my daily exercise last week wasn’t on my normal rowing machine but was spent dragging my old 1957 film camera (one of my more modern items of equipment) around the empty streets of London considering some of its more unusual historical landmarks.

My first impressions on wandering around the City were that it’s not entirely empty. There were still curious tourists wandering around and bikes, a lot of bikes - which appear to have largely taken over as a way of getting around. The sections around my office (just off Fleet Street) still seem like a normal city (albeit one having an off-day) but once you wander further into the deepest darkest part of the Square Mile things become different very quickly. There is no one on the streets and it feels like the whole place is abandoned. It's a particularly odd feeling given the normally busy offices and sandwich bars.

Stop 1 - Smithfield Market

My first stop on the historical walking tour is actually something of a cheat. The event I have come to think about didn’t really happen in the City but in the fields outside the City walls as they were then (in fact, the Smith Fields).

On 13 June 1381, a significant section of the population, frustrated at a social system that actively prejudiced them broke into London and began running amok. The reasons for the Peasants’ Revolt are wide and range from the social/economic factors caused by one of the worst global pandemics in history (the Black Death that killed an estimated 50% of England’s population) to perceived government mismanagement of various crises, war, over taxation and frustration at the system of serfdom that kept those subjected to it in poverty.

Even with the passing of almost 700 years, the sense of frustration and fear present in the City in those few days is palpable. The rebels had lists of people they wanted the young Richard II (only 14 at the time) to hand over for execution. They wandered the streets looking to enact vengeance where they could. Clerkenwell Priory was destroyed, Temple was attacked and its contents burned. Most audaciously, the rebels waited until the King had left to negotiate with their leaders at Mile End before entering the Tower of London. There they found key members of the King’s entourage (including the Archbishop of Canterbury and the treasurer) and beheaded them.

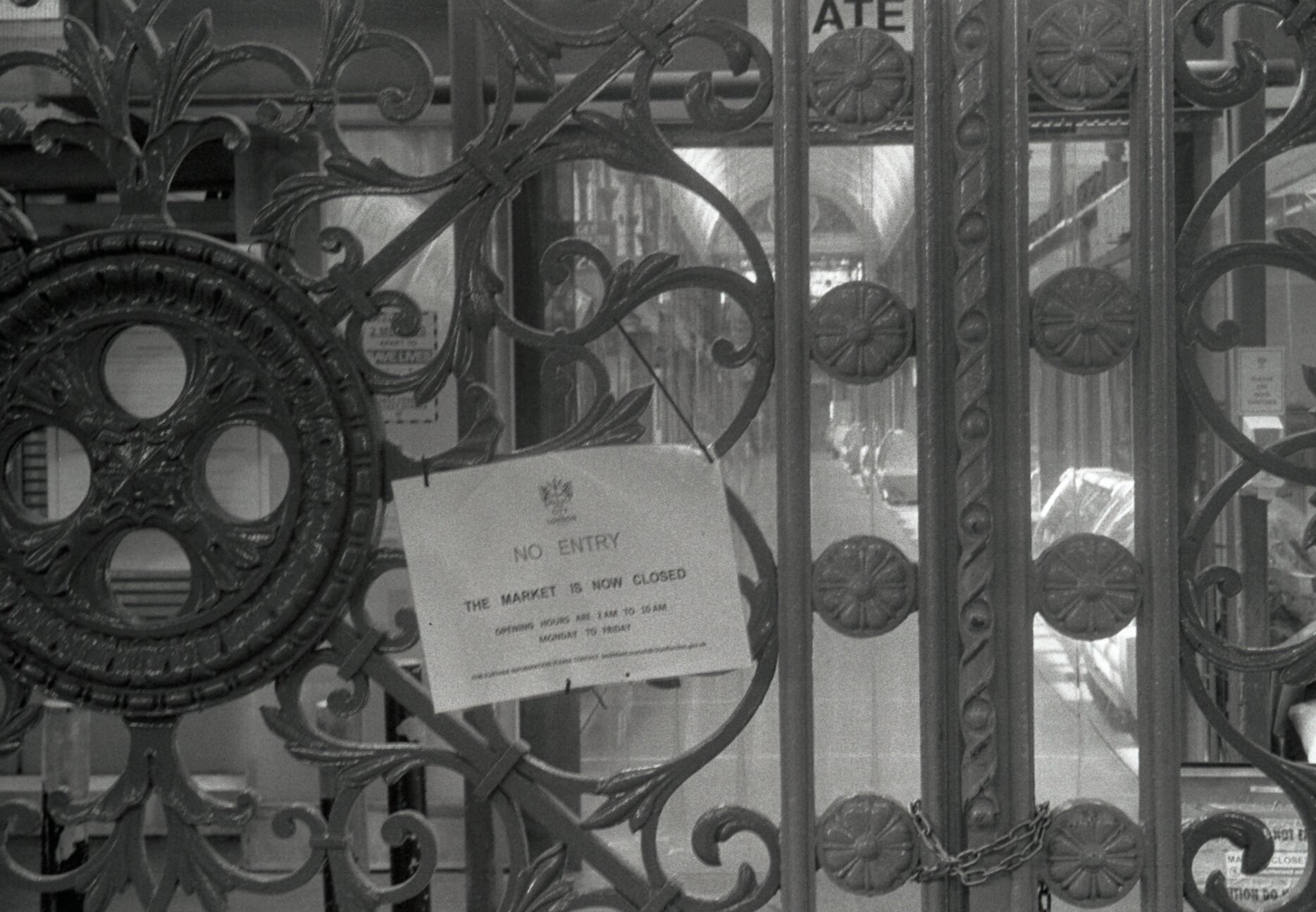

A deserted Smithfield market

By this point, the King had already agreed to many of the rebels' demands and was disappointed that they had refused to disperse. He met the rebels and their leader, Wat Tyler, outside of the City walls at Smithfield to protest at the fact they were still plaguing the City. The exact details of what happened are somewhat patchy but it seems that Tyler was overfamiliar with the King. He asked for water and then (in what always seems a somewhat incredibly bullish move):

The Peasant's’ Revolt memorial

“rinsed his mouth in a very rude and disgusting fashion before the King’s face”.

It must have been fairly extreme as there was a scuffle and the Lord Mayor of London stabbed Tyler before another of the King’s servants joined in on the act. Tyler was severally injured but, in the general commotion, ended up in a hospital for the poor before being dragged back to Smithfield and beheaded. In a remarkable move, the King managed to defuse the situation and persuade the rebels to disperse and, without their leader, the movement quickly fell apart. The King quickly clamped down on the rising, reversed his promises and rounded up and executed the key leaders of the revolt.

The historiography of the revolt is a particularly rich area with some claiming it as a proto-Marxist movement. Others have suggested it had lasting significance in changing the practice of serfdom and more still have stated it did very little indeed. Whatever the historical truth, it is still remembered in the small square in front of St Barts with a plaque that features a particularly poignant (and relevant?) quote from John Ball (a priest in the leadership of the rising who would later be hung, drawn and quartered in front of the King):

“Things cannot go on well in England, nor ever will, until everything shall be in common when there shall neither be vassal or Lord and all distinctions levelled.”

There are parallels so obvious between this event and our current time, it’s almost trite to draw them. A major biological catastrophe changing our daily lives, government advisors that spend more time in castles than serving the people and an important part of our society so disenfranchised by the establishment that they seek to topple some of the pillars that maintain the social order. Some things do not change, although perhaps they ought to.

Regardless, the City has endured despite the bloodshed of those few days in June and it was eerie to stand on the same sport in the middle of the normally bustling Smithfield area with only the shadows of the past for company.